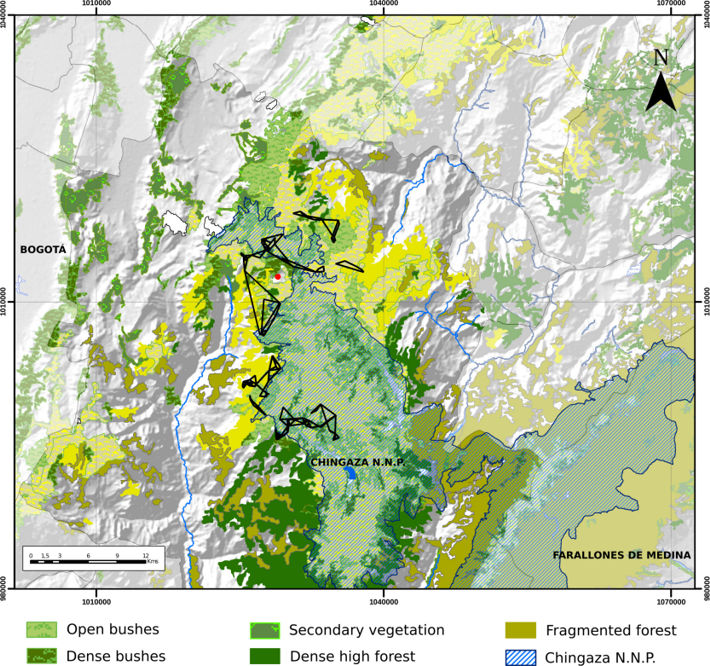

Space use by a male Andean bear (Tremarctos ornatus) tracked with GPS telemetry in the Macizo Chingaza, Cordillera Oriental of the Colombian Andes

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.31687/saremNMS.21.2.4Keywords:

Andean bear, core area, GPS telemetry, habitat, home rangeAbstract

For decades, telemetry has provided large amounts of ecological information for several bear species; however, for the Andean bear (Tremarctos ornatus), only three studies have available information. The use of space for this species was measured for the first time in Colombia with a male specimen tracked with GPS telemetry. Bear locations (n = 348) were obtained between October and December 2013, during the dry season. Our dry-season male home range estimates with nearest-neighbor convex-hull (K-NNCH, 24.62 km²) and kernel density estimate (KDE, 42.15 km²) slightly exceed those reported for the species in Ecuador, and our minimum convex polygon (MCP, 238.86 km²) quintupled estimates from Ecuador. This finding supports the hypothesis that more fragmented landscapes demand greater movements to obtain sufficient resources. K-NNCH and KDE were the most accurate methods, as they excluded degraded terrain not used by the tracked bear. Total daily traveled routes oscillated between 0.51–12.07 km. The forest-páramo ecotone, full of dry-season-fruiting Ericaceae shrubs, was the main habitat used.

References

Andreassen, H. P., K. Hertzberg, & A Rolf. 1998. Space-use responses to habitat fragmentation and connectivity in the root vole Microtus oeconomus. Ecology 79:1223–235.

Börger, L., B. D. Dalziel, & J. M. Fryxell. 2008. Are there general mechanisms of animal home range behavior? A review and prospects for future research. Ecology Letters 11:637–650.

Burt, W. H. 1943. Territoriality and home range concepts as applied to mammals. Journal of Mammalogy 24:346–352.

Calenge, C. 2015. Home range estimation in R: The adehabitatHR package. The comprehensive R archive network. <https://cran.r.project.org/web/packages/adehabitatHR/adehabitatHR.pdf>.

Castellanos, A. 2011. Andean bear home ranges in the Intag region, Ecuador. Ursus 22: 65–73.

Castellanos, A. 2013. Andean Bear Core Area Overlap in the Intag Region, Ecuador. Molecular Population Genetics, Evolutionary Biology and Biological Conservation of Neotropical Carnivores (M. Ruiz Garcia & J. M. Shotel, eds.). Nova Science Publisers Inc., New York.

Castellanos, A., L. Arias, D. Jackson, & R. Castellanos. 2010. Hematological and serum biochemical values of Andean bears in Ecuador. Ursus 21:115–120.

De Solla, S. R., R. Bonduriansky, & R. J. Brooks. 1999. Eliminating autocorrelation reduces biological relevance of home range estimates. Journal of Animal Ecology 68:221–234.

Evans, A., et al. 2012. Capture, anesthesia, and disturbance of free-ranging brown bears (Ursus arctos) during hibernation. PLoS ONE 7:e40520.

Fernández, S. A. 2012. Caracterización morfológica de Cavendishia bracteata y Macleania rupestris (Ericaceae) en la sabana de Bogotá. Bachelor's thesis, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia.

Fieberg, J. 2007. Kernel density estimators of home range: smoothing and the autocorrelation red herring. Ecology 88:1059–1066.

Figueroa, J. 2013. Revisión de la dieta del oso andino Tremarctos ornatus (Carnivora: Ursidae) en América del Sur y nuevos registros para el Perú. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales 15:1–27.

Garshelis, D. L. 2004. Variation in ursid life histories, is there an outlier? Panda conservation (D. Lindburg & K. Baragona, eds.). University of California Press, Berkeley.

Getz, W., & C. Wilmers. 2004. A local nearest-neighbor convex-hull construction of home ranges and utilization distributions. Ecography 27:489–505.

Heard, D. C., L. M. Ciarniello, & D. R. Seip. 2008. Grizzly bear behavior and Global Positioning System Collar fix rates. Journal of Wildlife Management 72:596–602.

Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales (IDEAM). 2013. Zonificación y codificación de unidades hidrográficas e hidrogeológicas de Colombia. IDEAM, Bogotá.

Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales (IDEAM). 2014. Cobertura de la tierra metodología Corine Land Cover adaptada para Colombia durante el periodo 2010–2012. IDEAM, Bogotá. <http://www.siac.gov.co/catalogo-de-mapas>.

Kays, R., M. C. Crofoot, W. Jetz, & M. Wikelski. 2015. Terrestrial animal tracking as an eye on life and planet. Science 348:aaa2478. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa2478.

Kernohan, B. J., R. A. Gitzen, & J. J. Millspaugh. 2001. Analysis of animal space use and movements. Radio tracking and animal populations (J. J. Millspaugh & J. M. Marzluff, eds.). Academic Press, San Diego.

Mergey, M., R. Helder, & J. J. Roeder. 2011. Effect of forest fragmentation on space-use patterns in the European pine marten (Martes martes). Journal of Mammalogy 92:328–335.

Millspaugh, J. J., & J. M. Marzluff. 2001. Radio tracking and animal populations. Academic Press, San Diego.

Mohr, C. 1947. Table of equivalent populations of North American small mammals. American Midland Naturalist 37:223–249.

Ofstad, E. G., H. Ivar, S. E. Johan, & S. Bernt-Erik. 2016. Home ranges, habitat and body mass: simple correlates of home range size in ungulates. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 283:20161234. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.1234.

Paisley, S., & D. L Garshelis. 2006. Activity patterns and time budgets of Andean bears (Tremarctos ornatus) in the Apolobamba Range of Bolivia. Journal of Zoology 268:25–34.

Parque Nacional Natural Chingaza (PNN Chingaza). 2005. Documento ejecutivo del plan de manejo del Parque Nacional Natural Chingaza 2005-2009. PNN Chingaza, Bogotá.

Peyton, B. 1980. Ecology, distribution and food habits of spectacled bear, Tremarctos ornatus, in Perú. Journal of Mammalogy 61:639–652.

Powell, R. A., & S. M. Mitchell. 2012. What is a home range. Journal of Mammalogy 93:948–958.

R Core Team. 2019. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available at: <http://www.R-project.org>.

Ríos-Uzeda, B., H. Gómez, & R. B. Wallace. 2006. Habitat preferences of the Andean bear (Tremarctos ornatus) in the Bolivian Andes. Journal of Zoology 268:271–278.

Rodríguez, D. 1991. Reconocimiento del hábitat natural del oso andino, Tremarctos ornatus, en el Parque Nacional Natural las Orquídeas, Antioquia, Colombia. Bachelor's thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia.

Rodríguez, D., et al. 2016. Desempeño de un collar GPS en el seguimiento a un oso andino (Tremarctos ornatus) en los Andes colombianos. Biodiversidad Neotropical 6:68–76.

Rodríguez, D., et al. 2019. Northernmost distribution of the Andean bear (Tremarctos ornatus) in South America, and fragmentation of its associated Andean forest and Paramo ecosystems. Therya 10:161–170.

Rodríguez, D., et al. 2020. Andean bear (Tremarctos ornatus) population density and relative abundance at the buffer zone of the Chingaza National Natural Park, cordillera oriental of the Colombian Andes. Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia. https://doi.org/10.11606/1807-0205/2020.60.30.

Sikes, R. S., & Animal Care and Use Committee of The American Society of Mammalogists. 2016. Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research and education. Journal of Mammalogy 97:663–688.

Troya, V. F., F. Cuesta, & M. Peralvo. 2004. Food habits of Andean bears in the Oyacachi River Basin, Ecuador. Ursus 15:57–60.

Velez-Liendo, X., & S. García-Rangel. 2017. Tremarctos ornatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T22066A123792952. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22066A45034047.en.

Verbeylen, G., L. A. Wauters, L. De Bruyn, & E. Matthysen. 2009. Woodland fragmentation affects space use of Eurasian red squirrels. Acta Oecologica 35:94–103.

Worton, B. 1989. Kernel methods for estimating the utilization distribution in home range studies. Ecology 70:164–168.

Yerena, E. 1987. Distribución pasada y contemporánea de los úrsidos en América del Sur. Departamento de Estudios Ambientales, Universidad Simón Bolívar, Caracas.

Zeller, K. A., D. W. Wattles, L. Conlee, & S. Destefano. 2020. Response of female black bears to a high density road network and identification of long-term road mitigation sites. Animal Conservation. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12621.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2021 Daniel Rodriguez, Adriana Reyes, Andrea del Pilar Tarquino-Carbonell, Héctor Restrepo, Nicolás Reyes-Amaya

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.